Introduction to Unix

(last update: Tue Sep 13 20:35:15 CEST 2016)

1 Course Information

This course is a 3-day intensive introduction to the Unix operating system, designed for an audience with no prior experience in Unix. The main objectives are:

- Learning the fundamental concepts behind the design of Unix

- Learning how to effectively use a Unix/Linux machine

- An updated version of the course will always be available at:

- http://lipn.univ-paris13.fr/~rodriguez/teach/unix/2016-17/

1.1 Instructor

César Rodríguez (http://lipn.univ-paris13.fr/~rodriguez)

1.2 Syllabus and Program

Day 1:

- Presentation

- Introduction: motivation, architecture, first steps with the terminal

- Unix file system: file types, absolute/relative paths, permissions, regular expressions

Day 2:

- Users and groups

- Processes: process attributes, file descriptors, redirections

- Signals

Day 3:

- Network: configuration, remote access, tools

- System administration: system boot, Debian package management, vi editor

- Shell scripting

1.3 Attendance, Grading, and other Policies

Our school publishes every year an updated version of the document "Modalités de contrôle de connaissances" (MCC). The MCC contains rules and policies applicable to this course, read them (starting from p. 106). The rules below in this section recall the basic principles of the MCC and extend the MCC when appropriate for this course.

Attendance. Attendance to all the course sessions is mandatory and will be accounted for the final grade of the course. The absence to a session (lecture or practical) can be justified with appropriate documents, such as medical certificates, delay certificates from the SNCF, or others. Those justifications shall be delivered to the "sécretariat", not the instructor.

Delays. A student will be considered late if he/she enters the classroom up to 30 min after the stating time (usually 8.30am or 1.45pm). A delay will be considered unjustified unless the student provides appropriate justifying documents (see previous paragraph) or explanations to the instructor (not the "sécretariat"). Each student has the right to 1 unjustified delay per course (12 sessions). Each unjustified delay starting from the 2nd will reduce 5% the overall course grade.

Being late for more than 30 min will be considered an absence for the entire session.

Grading. The final grade will be determined as follows:

Final course grade = Academic Grade * Attendance coef. * Delay coef.

Attendance coef. = 1 - 0.5 * (Unjustified absences / Number of course sessions)

Delay coefficient = 1 - 0.05 * (Unjustified delays - 1)

Academic grade = 0.2 * Continuous assessment +

0.2 * Shell script +

0.2 * Programming exercises +

0.4 * Network server exercise (small project)

Collaboration. Discussion, exchange of ideas, and mutual help for understanding complex concepts are key aspects of the learning process inside of a classroom, and as such they are strongly encouraged in this course. However, any submitted piece of work (exercise solution, program code, report, etc.) displaying the student's name must be the result of the student's original and individual work. Helping your peer to independently reach the solution to a problem or difficulty is acceptable. Passing or receiving the solution from your peer is not.

Collaboration between students (working in groups of two or more) shall be explicitly authorised by the instructor.

All program code produced for the various course assignments is expected to be your own creation. Verbatim copying from Internet webpages or any other sources is entirely disallowed. Taking inspiration to write your own code from code in manpages, tutorials, etc. is allowed under the condition that the source is cited in comments.

Inside the classroom. Using mobile phones, music players, or headphones is disallowed inside of the classroom.

1.4 Additional material

- Exercises: http://www.doc.ic.ac.uk/~wjk/UnixIntro/

- Debian Virtual Machine: available here.

2 Introduction

2.1 What is an operating system?

You should already be familiar by now (cf. "Administration de Windows" course), but here is a tentative definition:

- A set of software pieces whose goal is masking the ugly details of hardware resources by means of clean, high-level abstractions (e.g., files, processes, printers) enabling us to use and manage those resources easily and efficiently.

That is, the operating system presents computing hardware as an extended and virtual machine

2.2 Brief history of Unix

- Multics: high availability and scalability; many novel ideas, not a commercial success

- Ken Thompson writes Unix in assembler for the PDP7; Dennis Ritchie writes the first C compiler; they rewrite Unix in C, beginning of portability and expansion

- 80s: AT&T version (System V), and Berkeley version (BSD); industrial adoption and new branches

- 1988: first POSIX standard

- 1991: Linus Torvalds writes Linux and releases it as free software

- Many Linux distributions appear

- Linux everywhere: Android, network equipment (routers, access points), tablets, GPS navigation devices, Raspberry Pi, UAV autopilots, etc.

2.3 Architecture of a typical Unix system

- User programs

- Interact directly with the user

- Compilers, text editors, web browsers, games, ...

- System tools

- Standard programs for doing very basic operations: copying files, renaming files, searching the file system, printing, remote access client/servers, etc.

- Examples: ls, cp, find, grep, ssh

- Design principle: tools that perform single, specific tasks but which can easily be combined with others to solve more complex problems (rather than monolitic applications designed for a purpose)

- Among them we have the shell

- The kernel

- Loaded directly in memory by the boot loader

- Provides most of the abstractions that present hardware in a unified and clean way

- Technically, device drivers play the central role in building these abstractions

- Kernel mode vs user mode

- Hardware

- These are the computing resources managed by the operating system

2.4 The shells

Shells are regular, ordinary processes. They enable the user to execute other programs. Whenever you type the name of command/program in the shell, it may execute an internal command or an external command.

Internal commands are functions implemented directly in the shell program. The shell will not, in general, create a new process running the command. However, when you type the name of an external command, the shell will locate an external executable file of the same name and create a new process executing such program.

The list of directories which will be searched is stored in the PATH environment variable. Directories will be searched from left to right for an executable file whose name is equal to the command you typed:

$ echo $PATH /usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin

The (internal) command type can be used to display the location of an external command.

Finally, be aware that several shells are usually available in a Linux system:

- sh, the Bourne shell

- bash, the Bourne again shell

- csh, the C shell

In this course we will uniquely focus on the bash shell.

2.5 First Steps with the Terminal

Whenever you open a terminal, it shows a line of text similar to this:

cesar@polaris:~$

This is called the prompt. We can read it as follows:

- The currently connected user is cesar

- We are connected at machine polaris.

- Between the : and the $ we can see the current working directory, the folder at which the commands will be executed. Currently it is ~, a synonym for the folder /home/cesar/.

- The $ in the end tells the user that the shell is ready to accept a command.

You can now type a command (see exercise below). Commands have:

- Short options: ls -l -a

- Long options: ls --long --all

- Multiple options: ls -la

Exercise. Enter the following commands in the terminal and try to interpret the output. What are the following commands for?

echo hello world

passwd

date

ls

ls -l

hostname

uname -a

dmesg | less (you may need to press q to quit)

uptime

w

who

id

df

du -s -h /tmp

top (you may need to press q to quit)

echo $SHELL

echo {con,pre}-{sent,fer}/{s,ed}

man "automatic door"

man ls (you may need to press q to quit)

man who (idem)

man man (idem)

clear

cal 2014

bc -l (type quit or press Ctrl-d to quit)

echo 5+4 | bc -l

time sleep 5

history

Exercise. Certain characters have a special meaning for the shell. Which meaning?

' " `cmd` | > ;

Exercise. Locate the program file that will be executed when you type the command cp. Do not use the command type.

2.6 Getting Help

For internal commands (or shell builtins) use the command help, without arguments or followed by the name of the command for which you want help, for instance:

help pwd

For external commands, the main source of documentation is the manual, or the man pages. Use the command man to get access to the manual pages (manpages) of each (documented) command in the system. For instance, type:

man ls

(Type "q" to terminate the previous command.) The manual pages can be searched using the option -k (k for keyword) of the command man. For instance, search for all man pages whose description contains the keyword "search":

$ man -k search apropos(1) - search the whatis database for strings grep(1), egrep(1), ... - file pattern searcher ldapsearch(1) - LDAP search tool leaks(1) - Search a process's memory for unreferenced ... lkbib(1) - search bibliographic databases ...

The manual is organized in sections, or chapters:

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | General commands |

| 2 | System calls |

| 3 | Library functions, covering in particular the C standard library |

| 4 | Special files (usually devices, those found in /dev) and drivers |

| 5 | File formats and conventions |

| 6 | Games and screensavers |

| 7 | Conventions, Protocols, and Miscellanea |

| 8 | Administration and privileged commands and daemons |

Observe that only the first section is devoted to commandline tools, while the second and third describe C functions used for progamming in Unix. Some commands have the same name as well known functions, for instance, the command printf. We use the syntax printf(1) to refer to the man page of the tool printf in section 1, and printf(3) to refer to the documentation of the well known C function printf.

- Using the manual: format of the man pages, searching with / or ctrl+f

An online copy of most manpages available in Linux can be found at http://linux.die.net/man/.

3 File System

3.1 Types of files

Ordinary files

- Contain text, images, html documents, program data, etc.

$ ls -l /bin/cp -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 130304 Mar 10 20:10 /bin/cp

Directories

- Contain entries that point to files or other directories.

- Directories do not contain files, they contain entries that point to them

$ ls -ld /bin drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 12288 Aug 8 09:17 /bin

Devices

- Are abstractions of hardware devices, provide easy access to them

- There are two types

- Block-oriented: transfer data in blocks (disk)

- Character-oriented: transfer data in characters (terminals, mouses, modems, etc)

$ ls -l /dev/ram0 brw-rw---- 1 root disk 1, 0 Aug 29 15:24 /dev/ram0 $ ls -l /dev/tty0 crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 0 Aug 29 15:24 /dev/tty0

Hard and soft links

- Are pointers to other files. We will talk about these later in this chapter.

3.2 Standard Filesystem Hierarchy

| Directory | Function |

|---|---|

| / | The root directory |

| /bin | Essential command binaries that need to be available in single user mode; for all users, e.g., cat, ls, cp. |

| /boot | Boot loader files, e.g., kernels, initrd. |

| /dev | Essential devices, e.g., /dev/null. |

| /etc | System-wide configuration files |

| /home | Users' home directories, containing saved files, personal settings, etc. |

| /lib | Libraries essential for the binaries in /bin/ and /sbin/. |

| /media | Mount points for removable media such as CD-ROMs |

| /mnt | Temporarily mounted filesystems. |

| /opt | Optional application software packages. |

| /proc | Virtual filesystem providing information about processes and kernel information as files. In Linux, corresponds to a procfs mount. |

| /root | Home directory for the root user. |

| /run | Information about the running system since last boot, e.g., currently logged-in users and running daemons. |

| /sbin | Essential system binaries, e.g., init, ip, mount. |

| /srv | Site-specific data which are served by the system. |

| /tmp | Temporary files, often not preserved between system reboots. |

| /usr | Secondary hierarchy for read-only user data; contains the majority of (multi-)user utilities and applications. |

| /usr/bin | Non-essential command binaries (not needed in single user mode); for all users. |

| /usr/include | Standard include files. |

| /usr/lib | Libraries for the binaries in /usr/bin/ and /usr/sbin/. |

| /usr/src | Source code, e.g., the kernel source code with its header files. |

| /var | Variable files-files whose content is expected to continually change during normal operation of the system (logs, spool files, and temporary e-mail files). |

3.3 Absolute and Relative Paths

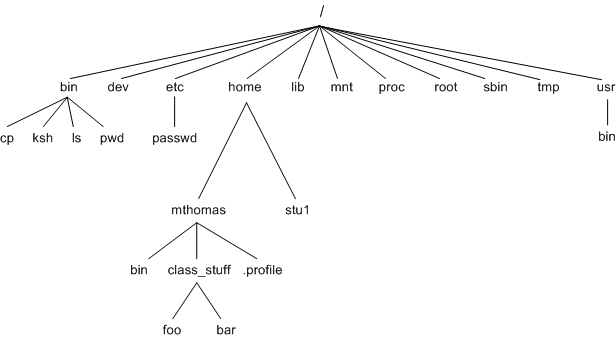

As we saw above, the file system in Unix is structured like a tree. The root of the tree is the directory /. Every file and directory is thus identified by a unique file path (the branch of the tree) that starts by /. Such path is called absolute path. Examples:

- /

- /bin/ls

- /bin/cp

- /etc/passwd

- /usr/include/stdio.h

Having to identify files by absolute paths starting from the root of the tree can sometimes be limiting. Hence the need for relative paths.

Every process running in a Unix system has an associated current working directory (CWD). The internal command pwd (print working directory) prints the CWD:

cesar@polaris:~$ pwd /home/cesar cesar@polaris:~$ cd /usr/bin/ cesar@polaris:/usr/bin$ pwd /usr/bin

A relative path is a file path which does not start by /. The file identified by a relative path is that resulting from appending the CWD and the relative path, for instance:

| CWD | Relative path | File/directory identified |

|---|---|---|

| /bin | ls | /bin/ls |

| /bin | cp | /bin/cp |

| /usr | include/stdio.h | /usr/include/stdio.h |

| /home | mthomas/class_stuff/foo | /home/mthomas/class_stuff/foo |

| /home/mthomas | class_stuff/foo | /home/mthomas/class_stuff/foo |

Each directory contains two special files, named . and ..; these "files" are in fact links to, respectively, the same directory, and the parent directory. This allows to to navigate the file tree also in the direction towards the root:

| Path (absolute in these examples) | File/directory identified |

|---|---|

| /bin/.. | / |

| /bin/../bin/ls | /bin/ls |

| /usr/bin/.. | /usr |

| /usr/bin/../.. | / |

| /bin/. | /bin |

| /bin/./cp | /bin/cp |

| /bin/./.. | / |

| /bin/./.././. | / |

| /bin/../usr/./bin/../include/stdio.h | /usr/include/stdio.h |

3.4 Commands: Browsing and Copying Files and Directories

The following commands (with the exception of cat, more and less) only allow to copy, move and remove files and folders.

pwd

Print Working Directory

This is an internal command of the shell. It prints the current directory from which relative paths will be interpreted.

The current working directory is also usually visible in the shell's prompt:

cesar@polaris:/usr/bin$ pwd /usr/bin

ls [-laihdR] [path1, path2, ...]

List directory contents

Options:

-l Long list. List attributes of a file, such as owner, permissions, size, etc. -a List all files, including also hidden files (those stating with a dot). -i Show the file's inode number (index number), see below. -h Display human readable sizes. Shows 1K instead of 1024, and 1M instead 1048576. -d List directory entries as if they were regular files, instead of listing their contents. -R Recursive listing of directories.

cd [path]

Change directory.

cp [-Rv] source target

Copy files and directories. By default cp only copies files and refuses to copy directories. With this option it also (recursively) copies directories.

Options:

-R Recursive copy. -v Displays the source/destination paths of files being copied.

mv source destination

Move/rename files and directories. Contrary to cp, mv does not need option -R to move/rename directories.

rm [-Rif] path

Remove files. By default rm refuses to remove directories. Option -R is necessary to (recursively) remove a directory.

Options:

-R Recursive removal. -i Ask the user for confirmation before removing any file. -f Ignore errors and continue.

mkdir dir

Make new directories.

rmdir dir

Remove directories. It will refuse to remove directories that are not empty.

cat [path1 path2...]

Concatenate and print files in the screen.

more [path...] and less [path...]

Paginate large files in the screen, more useful than cat to display large files in the screen.

find [path1 path2...] [expression]

The command find searches for files and directories within the file tree(s) starting at one (or more) directory path(s). The argument [expression] tells find which files we are searching for.

- If the path is missing, then the current working directory . is assumed.

- If the expression is missing, then the argument -print is assumed (see man page), which will cause find to print all files recursively found. Many other filters can be indicated in expression, see find(1).

Examples:

$ find /usr/ /usr/ /usr/bin /usr/bin/env /usr/bin/tzselect /usr/bin/test ... $ find /path/to/dir1 /path/to/dir2 ...

du [path...]

The command du (disk usage) recursively estimates the size of the files present in the subtree pointed by the given path. Important options: -s -h

Example:

$ du -sh /tmp 82M /tmp/

df

Displays the available free/used space in a disk.

Important options: -h

Exercises: http://www.doc.ic.ac.uk/~wjk/UnixIntro/Exercise2.html

- 5, 11, 12: don't do it

- 13 and 14: use the terminal device file identified in exercise 3

- 21: forget about the symbolic link

3.5 Inode Structure and File Permissions

Each file and directory in a UNIX file system has an associated structure containing administrative information such as the file owner, access rights, file size, and information about the disk sectors storing the file. This structure is called the index node, or inode of the file.

The inode contains at least the following fields:

| Field | Explanation |

|---|---|

| st_dev | ID of device (usually a disk) containing the file |

| st_ino | inode number |

| st_uid | ID of user owner |

| st_gid | ID of "group" owner |

| st_mode | Access rights |

| st_nlink | Number of hard links |

| st_size | File size, in bytes |

| st_atime | Time of last access |

| st_mtime | Time of last modification to file contents |

| st_ctime | Time of last status change (either content update or owner/permissions update) |

The filed st_ino stores a unique number identifying the file within the file system. This number is called the inode number, or, to make things more complex, also simply the inode.

The inode structure also stores the ID of the user to which the file belongs (field st_uid) and the ID of a group (of users) which have special access rights for the file (field st_gid). The field st_mode specifies the access rights for

- the user owning the file (st_uid),

- the group owning the file (st_gid), and

- any other user different than st_uid and not in the group st_gid.

For each one of these three, st_mode declares whether the user can

- read the file (list the contents if it is a directory),

- write the file (create new files if it is a directory), and

- execute the file (navigate across it or modify it if it is a directory).

The command ls -l displays ownwership and permission information about files in its first columns, for example:

$ ls -l /bin/cp - rwx r-x r-x 1 root root 130304 Mar 10 20:10 /bin/cp = === === === = ==== ==== ====== ============ ======= 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Field Example Stored in Explanation ====== ============= ========== ============================================== 1 - N/A Type of file: regular file 2 rwx st_mode Owner can Read, Write, and Execute 3 r-x st_mode Group can Read and Execute 4 r-x st_mode Other users can only Read and Execute 5 1 st_nlink There is only one hard link to the file 6 root st_uid User owner 7 root st_gid Group owner 8 130304 st_size File size, in bytes 9 Mar 10 20:10 st_mtime Date of last modification to file contents 10 /bin/cp N/A File path ====== ============= ========== ==============================================

In this example, the root user can read, write, and execute the file /bin/cp. Anyone in the group root (in fact, only the root user), can read and execute the file. And any other user of the system can also read and execute the file.

Let's take another example, a directory in this case:

cesar@polaris:~$ ls -ld /usr/bin/ drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 126976 Aug 28 10:54 /usr/bin/

Now, the first field displays a d for "directory". The directory belongs to the user "root" and to the group "root". The owner user can

- list files in the directory (read bit),

- create new files inside of the directory (write bit), and

- access files inside of the directory for read/write/execute operations (execute bit)

Users in the "root" group and any other user in the system can only list files in the directory and access them (if the permissions in the file's inode allows for it), but cannot create new files inside of the directory.

The command stat(1) prints the information stored in the inode structure of a file, and displays fields not shown by ls -l.

3.6 Commands: Modifying Permissions

id

The command id displays the name of the user invoking it, as well as the list of groups to which the user belongs. It will be useful for understanding which access rights you have for a file.

chmod mode path

This command changes the access rights of a file (inode field st_mode). Only the owner of a file can update the access rights. The argument mode specifies the new access rights for the file, and it is a sequence of three digits (user, group, others) from 0 to 7, using the following correspondence:

Permission Numeric representation --- 0 --x 1 -w- 2 -wx 3 r-- 4 r-x 5 rw- 6 rwx 7 So, this would be the output of ls -l after updating a file with the following modes:

chmod 644 file ==> rw-r--r-- chmod 755 file ==> rwxr-xr-x chmod 600 file ==> rw------- chmod 564 file ==> r-xrw-r--

chown [owner][:group] [path...]

This command changes the owner and group of a file. Examples:

chown cesar /tmp chown :floppy /tmp /bin/ls chown cesar:audio /bin/cp

Exercise.

- Create a file h.txt containing the text "hello world" in your home directory. Assign read/write rights to you and to no one else.

- Now, collaborate with the person sitting next to you to identify a group to which both of you belong. Change the group owner of your file to that group. Ask your mate if she/he can now read it.

- Now give read (but no write) permission to the group owner. Can he/she read/write it now? Now give it also write permission for the group. Can she/he now write?

- Ensure that the file has now permission 660. Change the group owner of the

file to one of the groups to which you belong

(find them with the command id).

Can your mate now read/write the file?

Change the permission so that he/she can

- read the file,

- write the file,

- both.

Exercise. Change your current directory to the /tmp directory. Create a directory d. Create a file f with some text inside of the directory. Now cd to your home directory. Make sure you can read the file (cat d/f) and list the files inside d (ls -l d).

Remove the execution rights for the directory owner.

- Can you now read the file?

- Can you list the files inside of d?

- Can you create a new file inside of d (example: echo hello > d/f1)?

Now remove the read rights for the directory.

- Can you read the file?

- Can you list the files inside of d?

Put back the read and execution permissions in the directory. Remove the write permissions.

- Can you now read the file?

- Can you list the files inside of d?

- Can you create a new file inside of d?

Remove the directory d and all its contents without accepting complains from the command rm.

3.7 Hard and Soft links

Every file and directory in the file system is uniquely identified by the inode number, stored in the inode structure (field st_ino). Option -i of the command ls displays this number (first column):

$ ls -li /usr/bin/ total 19424 396972 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 6216 Dec 11 2012 addpart 402848 lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 6 Jun 18 2012 apropos -> whatis 397423 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 122080 Oct 17 2014 apt-cache ...

In the UNIX file system it is possible to make appear the same file within two directories. This is called a hard link, and it is possible due to the internal structure in which directories are stored. We use the command ln to achieve this:

ln original destination

Obseve that this does not create a copy of the file original, it only creates a second directory entry that refers to the same original file. Both the original and destination file share the same inode, in contrast to copying a file with cp, which creates a new inode for destination file.

The UNIX file system provides a second way of creating directory entries that refer to the same file. These are called soft links:

ln -s original destination

In this case ln creates a new file (new inode, new directory entry) but the file is marked with an special flag and stores only the absolute path to access the original file. Soft links are very similar to Windows' shortcuts.

Exercise. Copy the file /bin/ls to your home directory, using the command cp, and give it the name myls.

- Which ownership and permissions had the original file?

- And the new file?

- Are the inode numbers different/equal?

Make three copies of myls, one with cp, another with ln (hard link) and another one with ln -s (soft/symbolic link).

- Which inode numbers are equal?

- What is the number of hard links of each of the four files (original + 3 copies)?

- Remove original file myls.

- Any change in the number of hard links?

- Can you now read the soft link?

3.8 Shell Tricks: Specifying Multiple Files with Wildcards

The shell interprets certain characters in a special way. Among those we find the following:

- ?

- Matches a single character.

- *

- Matches zero or more characters.

- [abc]

- Matches all characters enclosed between [ and ], in this case a, b, and c. It is possible to use hyphens to define classes, as in [a-z0-9]: all low-case letters and all 10 digits.

- {one,two,three}

- Matches the words one, two and three.

Examples:

| Wildcard | Matches |

|---|---|

| ??? | All file names three-letters long |

| * | All files in the current folder |

| *a* | All file names which contain the letter a |

| j*.png | All files starting with j and ending with .png |

| [A-Z]* | All files whose name starts with a capital letter |

| {/usr,}{/bin,/lib}/file | Expands to /usr/bin/file, /usr/lib/file, /bin/file, and /lib/file |

3.9 Commands: Handling File Contents

cat [path1 path2...]

Concatenates and prints files to the terminal.

hd [path...]

Prints a file in hexadecimal format. Useful for examining the contents of a binary file:

cesar@polaris:~$ hd /etc/passwd 00000000 72 6f 6f 74 3a 78 3a 30 3a 30 3a 72 6f 6f 74 3a |root:x:0:0:root:| 00000010 2f 72 6f 6f 74 3a 2f 62 69 6e 2f 62 61 73 68 0a |/root:/bin/bash.| 00000020 64 61 65 6d 6f 6e 3a 78 3a 31 3a 31 3a 64 61 65 |daemon:x:1:1:dae| 00000030 6d 6f 6e 3a 2f 75 73 72 2f 73 62 69 6e 3a 2f 75 |mon:/usr/sbin:/u| 00000040 73 72 2f 73 62 69 6e 2f 6e 6f 6c 6f 67 69 6e 0a |sr/sbin/nologin.| [...]

file [path...]

Guesses the type of the contents of a file.

Example:

cesar@polaris:~$ file /bin/ls /usr/share/man/man1/ls.1.gz /bin/ls: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, [...] /usr/share/man/man1/ls.1.gz: gzip compressed data, from Unix, max compression

head -n number [path...]

Prints the first number lines of a file:

cesar@polaris:~$ head -n3 /etc/passwd root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash daemon:x:1:1:daemon:/usr/sbin:/usr/sbin/nologin bin:x:2:2:bin:/bin:/usr/sbin/nologin

tail -n number [-f] [path...]

Prints the last lines of a file.

wc [-c] [-w] [-l] [path...]

Prints number of characters (-c), words (-w), or lines (-l) in a file:

cesar@polaris:~$ wc -l /etc/passwd 41 /etc/passwd cesar@polaris:~$ wc -c /etc/passwd 2189 /etc/passwd

sort [-nru] [path...]

Sorts the lines of a text file. By default sort orders the lines alphabetically. Options -n and -r change this behavior.

Options:

-n Assumes that lines start by a number and uses a numeric sorting instead of alphabetic order. -r Reverse sorting. -u Remove duplicated lines ("u" for "unique")

3.10 Mounting New Disks

Mounting and dismouting disks allows to insert and remove subtrees from the root filesystem (main tree).

Run the command mount without arguments to display the mounted file systems:

$ mount proc on /proc type proc (rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime) udev on /dev type devtmpfs (rw,relatime,size=10240k,nr_inodes=13785,mode=755) /dev/disk/by-uuid/bdc...07f on / type ext4 (rw,relatime,...) ...

The file /etc/fstab contains a list of devices and mount points known to the system. Traditionally, this file was used to know where to automatically mount removable media such as CD-ROMs or floppy disks:

$ cat /etc/fstab /dev/fd0 /mnt/floppy auto rw,user,noauto 0 0 /dev/hdc /mnt/cdrom iso9660 ro,user,noauto 0 0

mount [-t fstype] [-o options] device dir

Attaches the file system stored in the disk designated by the file device to the directory dir (mount point).

- umount {dir|device}

Deattaches a currently attached filesystem, provided the mount point or the device storing the file system.

It is very important to unmount (non read-only) file systems before removing the associated device from the system (USB disk, floppy, etc).

3.11 Regular Expressions

A regular expression is an expression that denotes a set of character strings.

To some extent, regular expressions are similar to arithmetic expressions, such as 4 * 5 or (3 / 4) + 7. An arithmetic expression combines basic terms (numbers) with certain operators (such as + or /) and represents a number (the result of the operation).

Similarly, a regular expression combines basic terms (character strings) with basic operators (see below) and represents a set of character strings:

Here are the most important operators used for regular expressions in Unix:

- ^

- Matches the beginning of a line.

- $

- Matches the end of a line.

- .

- Matches any character.

- [abc]

- Matches one of the characters listed inside of the brackets, in this case, either a, b, or c.

- EXPR?

- The preceding expression EXPR is optional, that is, matched 0 or 1 times.

- EXPR1|EXPR2

- Matches a string either matched by EXPR1 or by EXPR2.

- *

- The preceding item will be matched zero or more times.

- +

- The preceding item will be matched one or more times.

- ( and )

- Parenthesis can be used to apply one operator to a larger expression.

- \

- Turns off the interpretation of the following special character.

Examples:

| Expression | Matches |

|---|---|

| ^a | Any line starting with a. |

| ^a$ | Any line containing exactly the character a. |

| ^...$ | Any line containing exactly 3 characters. |

| ab?$ | Any line ending either by a or by ab. |

| c(ab)?$ | Any line ending either by c or by cab. |

| \.$ | Any line terminating with a dot (.) |

| ax*z | az, axz, axxz, axxxz... |

| [Cc][eé]sar | Either Cesar or César or cesar, or césar |

| [ab]*x | Any sequence of zero, one, or more characters taken from the set {a, b}, followed by one x. |

egrep [-iqvR] [-ABC num] [--color] expression [files...]

The tool egrep takes as argument a regular expression and a file. It evaluates the expression over each line of the file. If the line contains a substring matched by the expression, it prints the entire line. If not, it discards the line.

- Important: use ' around the expression to prevent the shell from interpretting the special characters of a regular expression

Options:

| -i | Case insensitive matching. |

| -q | Do not output matched lines. Instead, exit immediately with zero status if a match is found. |

| -v | Invert the matching, that is, print lines not matching the expression. |

| -R | Match against all files recursively found in a directory. |

| -A num | Print "num" lines after each line matched. |

| -B num | Print "num" lines before each line matched. |

| -C num | Print "num" lines before and after each line matched. |

| --color | Colorize the substring of the line that was matched by the expression. |

3.12 Commands: Archiving and Compressing Files

3.12.1 Archiving

Creating a tar file:

tar cvf file.tar folder1/ folder2/

- c for create

- v for verbose (optional)

- f for file (i.e., the following argument is the tar file to create)

This creates the file archive.tar.

Listing the contents of a tar file:

tar tvf file.tar

- t for table or list

Extracting the files packed in a tar file:

tar xvf file.tar

- x for extract

This will recreate the directory structure packed into the tar file.

3.12.2 Compressing

Any file can be compressed with the gzip and gunzip tools:

$ ls -lh total 112K -rw-r--r-- 1 cesar cesar 112K Sep 9 18:52 file.txt $ gzip file.txt $ ls -lh total 52K -rw-r--r-- 1 cesar cesar 51K Sep 9 18:52 file.txt.gz

Uncompressing:

$ gunzip file.txt.gz $ ls -lh total 112K -rw-r--r-- 1 cesar cesar 112K Sep 9 18:52 file.txt

The tar tool can also automatically compress and decompress tar files with the flag z. For instance, creating and compressing a tar file, and subsequently decompressing it (in the /tmp directory):

tar czvf file.tar.gz folder1/ folder2/ tar xzvf file.tar.gz -C /tmp

The commands zip and unzip can produce and unpack the usual .zip files that are popular among Windows users.

Exercises: From http://www.doc.ic.ac.uk/~wjk/UnixIntro/Exercise3.html, do the following exercises:

- 7 to 10 (tail, find)

- 13 (locate)

- 14 (grep)

- 16 (dev files, od)

- 17 (mount)

4 Users and Groups

- Users

- Groups

- Superuser (root)

- Becoming superuser, su, prompt

4.1 System Files

- /etc/passwd

- /etc/shadow

- /etc/group

4.2 Commands: Managing Users and Groups

adduser username -- Interactively adds a user to the system

addgroup group -- Adds a group to the system

passwd -- Modifies user's password

To remove users and groups, use the commands deluser and delgroup.

Exercise: Use grep to isolate the line in /etc/passwd that contains the login details of the user syslog.

5 Processes

- A program is a binary file, containing executable instructions and data

- A process is an instance of a program in execution

- Processes are created with the system call fork(2).

- The parent process uses the system call wait(2) to wait for children to terminate and receive their exit code

Processes thus form a tree, where the root of the tree is the so-called init process, with PID 1.

5.1 Process Attributes

Here are the main attributes that each process has:

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| PID | Process ID, an integer number that uniquely identifies the process |

| PPID | Process ID of the parent process |

| State | Scheduling state, essentially runnable, sleeping, or stopped (see below) |

| Priority | Positive or negative integer affecting the process scheduling |

| UID | ID of the user owning the process |

| File descriptor table | Table describing the files currently opened by the process |

| Environment variables | List of pairs variable=value communicated to the process from the parent process |

| PGID | Process Group ID, an integer number uniquely identifying the process group to which the process belongs |

| SID | Session ID, unique integer identifying the session |

| Controlling Terminal | The terminal from which the process was started. Relevant for signal management. |

The attribute state can have the following values:

| State | Description |

|---|---|

| R | Running or runnable (on run queue) |

| D | Uninterruptible sleep (usually IO) |

| S | Interruptible sleep (waiting for an event to complete) |

| T | Stopped, either by a job control signal or because it is being traced. |

The priority is an integer ranging from -20 to 19. The (numerically) lower this value is, the most favourable the operating system scheduler will be to run the process in the presence of other processes in the runnable state.

The UID is used to determine the process permission to, for instance, access files.

The content of the file descriptor table and the environment variables for a given process can be retrieved from the /proc file system (as well as the values of most its the attributes):

- /proc/PID/fd/: file descriptor table

- /proc/PID/environ: environment variables

See the manpages proc(5) and ps(1) for more information.

A process belongs to a proces group, identified by the attribute PGID. A session is a set of process groups. Each process group is in at most one session. A session is associated with zero or one controlling terminal (every terminal is associated with exactly one session).

These three notions are mechanisms offered by Unix to implement useful features of the system. For instance:

- Whenever the user logs out, all processes initiated by him/her and currently running should be killed. Unix achieves this by sending the SIGHUP signal to all processes in the session associated to the controlling terminal. The default handler for SIGHUP terminates the process.

- Whenever the user types Ctrl+C, Unix sends the signal SIGINT to every process in the so-called foreground process group (see below). The default handler for SIGINT terminates the process.

A process (beloging to a group which is in a session) without controlling terminal is called a daemon.

Whenever a process exits, it sends to the parent process an exit status, an integer between 0 and 255 that is usually employed to indicate how the process terminated. An exit status 0 usually indicates that the process terminated normally, while a non-zero exit status indicate abnormal termination. The manpage of the program usually contains a description of the different exit values.

5.2 File Descriptors, Shell Redirections, and Pipelines

Whenever a process opens a file, the operating system assigns a number to the file and returns it to the process, which will use it to identify the opened file in subsequent operations. This integer is called the file descriptor.

File descriptors are indexes of a table which maps them to opened files. The same file can be opened twice, thus being accessible via two file descriptors. Such table is the file descriptor table.

By default, the first three file descriptors (indexes 0, 1, and 2 of the table) are opened and have specific well-known names:

- 0, standard input, or stdin (open read-only)

- 1, standard output, or stdout (open write-only)

- 2, standard error output, or stderr (open write-only)

When the shell forks a new command, by default all three descriptors access a single file: the device file associated with the terminal, a special character-oriented device file located in the /dev/ directory. (In turn, such device file represents the keyboard and the screen for a phisical user; or the endpoints of a TCP connection for a remote user; other configurations are possible.)

The shell provides mechanisms change such default behaviour, called redirections and pipes.

Redirect standard output to file out; leave unmodified standard input and error output (i.e., they are still attached to the terminal device):

$ COMMAND > out

Read standard input from file f instead of the terminal (they keyboard); leave unmodified standard and error output:

$ COMMAND < f

Redirect standard error output:

$ COMMAND 2> out

Of course we can combine the previous operators:

$ COMMAND < in > out

Other redirections are possible:

| Redirection | Explanation |

|---|---|

| [n]< file | Redirect file file to stdin; n is 0 if missing |

| [n]> file | Truncate file file and redirect stdout to it; n is 1 if missing |

| [n]>> file | Open file for writing and append stdout output to it; n is 1 if missing |

| [n]>&m | Redirect output to descriptor n to descriptor m; n is 1 if missing |

(More information in the bash(1) manpage, section "Redirections".)

Apart from redirecting input or output to a file, it is also possible to redirect inputs or outputs to another process, using a pipe.

Redirect the standard output of cmd1 to the standard intput of cmd2; leave unmodified the other inputs or outputs of both processes:

$ cmd1 | cmd2

The shell will create one process for executing the program cmd1 and another one for executing cmd2. The operating system provides a specific system call (see manpage pipe(2)) giving access to a channel-like data structure allowing to implement this functionality. The shell will connect both ends of this channel to the corresponding descriptors of both processes and then will let each process execute the corresponding program (which will transparently use the pipe instad of the terminal).

5.3 Environment Variables and Shell's Variables

UNIX provides a mechanism to communicate a number of pairs of form variable=value to a process. This is usually employed to transfer configurations to a newly created process. Usually a process receives at least the following variables:

- USER: The name of the logged-in user

- HOME: His her home directory

- PATH: A list of directory that the shell will search for programs to execute upon typing an incomplete pathname as command

- PWD: The current working directory

See environ(7) for more information.

A copy of this environment table is passed to every child process forked by a process. A process can, before or after forking new processes, modify this table using specific functions of the C library.

The shell provides a mechanism to store and update the so-called shell variables, a list of pairs variable=value different from the envioronment table. You set a shell variable using the syntax:

$ TEST="hello world" $ echo $TEST hello world

The variable is subsequently available using the syntax $VAR, as shown above. A shell variable is by default not copied to the shell's environment table, and so it is not visible in the environment table if subsequently forked processes.

However, a variable can be copied to the environment table. The internal command export copies a shell variable to the shell's environment, thus modifying the environment table that subsequent commands will receive:

$ TEST="hello world" $ env | grep TEST $ export TEST $ env | grep TEST TEST=hello world $ export -n TEST $ env | grep TEST

The (external) command env, run without arguments, allows you to see the environment being passed to a command. Observe that export -n removes the variable from the shell's environment table.

It is also possible unset a shell variable (it will also be removed from the shell's environment):

$ unset TEST

5.4 Commands: Processes Management

ps [axuj] [PID] -- Report a snapshot of the current processes

By default ps only selects processes from the calling user that have controlling terminal.

- a: lift the filter "only your processes"

- x: lift the filter "only processes with controlling terminal"

In combination both options (ax) select all running processes. Options u and j select the columns to display:

- u: display "user-oriented" format

- j: display "BSD job control format"

pstree -- Visually display the tree of processes

top -- Interactively display running processes

nice -n prio command -- run a program with modified scheduling priority

kill -9 PID -- send signal 9 (KILL) to process PID

killall -9 name -- kill a process by name

sleep nr -- waits for nr seconds

true and false (internal commands)

5.5 Shell Tricks: Foreground and Background commands

By default, whenever the user executes a command, the shell waits for the command to finish before it shows again the prompt, asking for a new command. We say that such command is a foreground command. The shell also offers a mechanism to launch background commands. In this case, the command will be executed in the background and the shell will immediately display the prompt, potentially before the command finishes. This is useful, e.g., to run commands that take long time to execute.

The operator & tells the shell to start a background command. The internal command jobs lists the currently running commands:

$ find / > output.txt 2> errors.txt & [1] 14785 $ jobs [1]+ Running find / > output.txt 2> errors.txt & $ ps u USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND 1087 14785 10.4 0.2 11904 1180 pts/3 D 14:55 0:02 find / 1087 14799 0.0 0.6 79396 3040 pts/3 R+ 14:55 0:00 ps u 1087 22536 0.0 1.3 82920 6736 pts/3 Ss 11:34 0:00 -bash

Observe that immediately after entering the find command, the shell launcehs job number [1] and prints the PID of the process (wich we see below after running ps).

A command launched in background can be brought to foreground using the internal command fg:

$ jobs [1]+ Running find / > output.txt 2> errors.txt & $ fg 1 find / > output.txt 2> errors.txt

Observe that now the shell does not show the prompt and instead waits for find to finish.

It is also possible to put in the background a command launched as a foreground processes (using the bg command). To learn about it we first need to learn about suspending (temporarily stopping) the execution of commands and also about signals (next chapter).

When a process in background terminates the shell will display so in the terminal. The process could naturally terminate, or could be killed by a signal:

$ find / > output.txt 2> errors.txt & [1] 16585 $ kill 16585 [1]+ Terminated find / > output.txt 2> errors.txt

It can also be brought to foreground, with fg, and terminated with Ctrl+C.

Process groups are the enabling mechanism that UNIX provides to implement foreground and background process management. Without entering details, each shell job (foreground or background), corresponds to a process group. Recall that a command could require launching several process, for instance a command using pipes. It therefore corresponds to a process group, not only one process

The bash shell provides relevant informations about the notions learned in this chapter via certain shell (pseudo-)variables (which it automatically updates):

- $

- PID of the shell

- ?

- Exit status of the last executed command

- !

- PID of the most recently executed background command

Examples:

$ sleep 100 & [1] 18399 $ sleep 200 & [2] 18400 $ echo $! 18400 $ false $ echo $? 1 $ true $ echo $? 0

Exercise: Use find and grep and sort to display a sorted list of all files in the subdirectory tree /usr/share that contain the word "hello" somewhere inside them.

Exercises: http://www.doc.ic.ac.uk/~wjk/UnixIntro/Exercise4.html

- do all of them!

6 Signals

Signals are a UNIX mechanism for asycnhronous inter-process communication. A signal is a notification sent to a process that stops its normal flow of execution to run, if registered, the signal handler associated to the signal.

Signals are sent in UNIX for various reasons, including:

- Certain hardware interrupts trigger the sending of a signal to a process

- Harware failures: power loss, illegal memory access, illegal CPU instruction

- Notifications related to asynchronous input/output

- Termination of child process, suspension of a process

The manpage signal(7) provides a general introduction to signal management in UNIX, as well as additional pointers to the manual.

- Principle: handler defined for a signal

- Default actions: ignore, terminate, core, stop, continue

| Signal | Value | Action | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIGHUP | 1 | Term | Hangup detected on controlling terminal or death of controlling process |

| SIGINT | 2 | Term | Interrupt from keyboard |

| SIGQUIT | 3 | Core | Quit from keyboard |

| SIGILL | 4 | Core | Illegal Instruction |

| SIGABRT | 6 | Core | Abort signal from abort(3) |

| SIGFPE | 8 | Core | Floating point exception |

| SIGKILL | 9 | Term | Kill signal |

| SIGSEGV | 11 | Core | Invalid memory reference |

| SIGPIPE | 13 | Term | Broken pipe: write to pipe with no readers |

| SIGALRM | 14 | Term | Timer signal from alarm(2) |

| SIGTERM | 15 | Term | Termination signal |

| SIGUSR1 | 30,10,16 | Term | User-defined signal 1 |

| SIGUSR2 | 31,12,17 | Term | User-defined signal 2 |

| SIGCHLD | 20,17,18 | Ign | Child stopped or terminated |

| SIGCONT | 19,18,25 | Cont | Continue if stopped |

| SIGSTOP | 17,19,23 | Stop | Stop process |

| SIGTSTP | 18,20,24 | Stop | Stop typed at tty |

| SIGTTIN | 21,21,26 | Stop | tty input for background process |

| SIGTTOU | 22,22,27 | Stop | tty output for background process |

6.1 Commands: Signal Management

kill -signal pid -- send signal signal (number or name) to process pid

trap handler signal -- sets shell function handler as handler of signal signal (number of name)

6.2 Shell Tricks: Job Control Revisited

We already know that typing Ctrl+C while a command executes in foreground normally terminates the command. In fact, what happens in this case is that the kernel sends a SIGTERM signal to all processes in the foreground process group associated to that terminal. The default action for SIGTERM is to terminate the process, although it is possible to define an alternative hanlder or even ignore this signal.

In contrast, the signal SIGKILL cannot be ignored or caught, and will invariably terminate the process.

Processes in UNIX can also be suspended (temporarily paused) and restarted by means of, respectively, signals SIGSTP and SIGCONT. Upon reception of SIGSTP, the process execution stops indefinitely. The process can choose to ignore or catch (define a handler for) SIGSTP, thus overriding its default behaviour. Signal SIGSTOP also stops the process, but cannot be caught or overriden. Process execution resumes upon reception of SIGCONT.

There are several ways of sending signals SIGSTP and SIGCONT to a process. One way is of course manually doing it with the kill command. UNIX (more specifically, the kernel together with the shell) provides a less cumbersome way:

- Whenever a process runs in the foreground and the user types Ctrl+Z, the signal SIGSTP is sent to every process in the foreground process group

- Two shell commands allow to to resume a suspended processes:

- Internal command fg resumes an stopped job in the foreground

- Internal command bg resumes an stopped job in the background

Example:

$ sleep 200 ^Z [1]+ Stopped sleep 200 $ jobs [1]+ Stopped sleep 200 $ bg 1 [1]+ sleep 200 & $ fg 1 sleep 200 ^C

7 Networking and Remote Access

- Priviledged ports

netstat [-tuanlp]

Print network connections, routing tables, interface statistics, etc.

netcat

Establish arbitrary TCP and UDP connections.

Can act as a TCP client and server. As a client:

netcat -v www.google.fr 80

As a server:

netcat -vnl 1234

wget URL

This command can download files from the Web using FTP/HTTP/HTTPS connections. It has plenty of options to configure the download process, the HTTP/FTP requests, and what to do with the downloaded files.

Example:

wget -O - 'http://lipn.univ-paris13.fr/~rodriguez/teach/unix/2016-17/' | grep course

7.1 Configuring the network interfaces

ifconfig -a ifconfig eth0 [up|down] ifconfig eth0 192.168.0.2 netmask 255.0.0.0

7.2 IP route table

route -n route add default gw 192.168.1.1 eth0

7.3 DNS

dig /etc/resolv.conf

7.4 DHCP, ARP

dhclient eth0 arp -na

7.5 Remote Access

ssh [-Xv] [-p port] user@host [COMMAND]

8 System Administration

8.1 Debian package managers

The Debian package management tools are essentially composed of two main collections of tools:

- the dpkg tool (the main Debian package management program)

- the APT (Advanced Package Tool) toolset

Packages are files with extension .deb. They contain

- Control information about the package (name, version, description, packages it depends on, conflicts with, cryptographic sums, and others)

- Scripts to execute upon, for instance, installation, upgrade, or removal of the package

- The actual contents to be installed

The dpkg(1) program is the actual tool that performs basic operations with the package, including

- Installing / uninstalling the package

- Printing control information

- Unpacking (without installing) the package

The APT toolset mainly includes two tools, apt-get(1) and apt-cache(1). The first tool is used to install and uninstall packages, together with the packages they depend on. The second one can be used to search on the list of packages that can be installed in your system.

- Sources of software defined in the file /etc/apt/sources.list

Here we give a list of the most commonly used commands:

Displaying the list of installed packages:

dpkg -l

Displaying the list of (installed) files for the package wget:

dpkg -L wget

Searching for the keyword tcp in the (local) list of candidate packages for installation:

apt-cache search tcp

Displaying the (control) information for the package netcat:

apt-cache show netcat

Updating the list of packages that can be installed in your system:

apt-get update

Installing package netcat:

apt-get install netcat

Uninstalling package python3:

apt-get remove python3

Updating to its latest version any package currently installed:

apt-get upgrade

Quite often you wish to know the package that provides certain tool that you need to use. Fortunately it is also possible to search for the files contained inside of packages. For Debian and Ubuntu, a search-inside-the-package search engines is available:

8.2 The vi text editor

- Command mode / insert mode

- :help

- i h j k l dd

- :w

- :q

8.3 The sed stream editor

The sed tool is a stream editor. Unlike other text editors, where the user edits a file interactively, a stream editor has a simple "program", or "script" that describes the modifications to be performed to the text file.

The basic syntax is as follows:

sed -e SCRIPT [FILE]

If FILE is not provided, sed will will act as a classic Unix filter (it will read from stdin and write outputs to stdout).

The SCRIPT is a sequence of commands, and the sed(1) manpage contains a list of accepted commands. Perhaps the most common command (and the only one we will show here) is the "substitution command", of the form

s/REGEXP/REPL/FLAGS

which substitutes the first occurrence of the regular expression REGEXP on every line by the text REPL, and where FLAGS is a sequence of option letters including:

- g: replace all occurrences of REGEXP in one line, instead of only the first

- i: match REGEXP in a case-insensitive manner

Here are some examples.

Get the UID of the user cesar:

grep '^cesar:' /etc/passwd | sed -e 's/^cesar...//' | sed -e 's/:.*//'

Do ls -l on every directory included in the PATH:

ls -l `echo $PATH | sed -e 's/:/ /g'`

List the PIDs of all processes of user cesar currently running:

ps axu | grep ^cesar | sed -e 's/^[^ ]* //' | sed -e 's/^ *//' | sed -e 's/ .*//'

Or even simpler:

ps axo user,pid | grep cesar | sed -e 's/^.* //'

9 Shell scripting

- Command line substitution

- true, false, test, expr

- if, while, case

- set -x

- basic sed

Follow http://www.doc.ic.ac.uk/~wjk/UnixIntro/Lecture8.html.

Exercises. http://www.doc.ic.ac.uk/~wjk/UnixIntro/Exercise8.html

- All exercises above except number 2.

Exercise. Write a script that receives only one argument, a path to a directory. Your script will determine the type of the file for each file recursively found in the directory, with the followng simplifications:

| Type of file | Your script will print |

|---|---|

| Ordinary files | "ordinary" |

| Directories | "directory" |

| Device (character) | "char" |

| Device (block) | "block" |

| Soft link | "link" |

| Any other type | "other" |

The output format of the script should look like this:

directory . ordinary ./script.sh directory ./mydir/ link ./mydir/mylink char ./mydir/ttys003 ...

On the following situations, your script should print to the standard error output an error message and terminate with exit code 1:

- If the script receives zero or more than one command-line argument

- If the argument passed to the script is not a file or a directory