A blockchain is a growing list of records containing information, called blocks, that are linked using cryptography principles. Each record / block contains a hash (some kind of signature) of the previous block, a timestamp, and transaction data generally represented as a Merkel tree (see below for an introduction).

A blockchain is "an open, distributed ledger (libro debitori e creditori) that can record transactions between two parties efficiently and in a verifiable and permanent way". Distributed is an important word in the previous sentence. It means that the "knowledge" of something is shared and spread over peers. Peers comunicate with messages. There is no central element for storing all the data. Open means that everyone can contribute to the development and maintenance of blockchain -- just like TCP/IP.

With the rise, a long long time ago, of what we call the "sedentary merchant" (understood in contrast to the earlier "traveling merchant" who accompanied his own goods to market or tradefairs), the medieval "commercial revolution" in Europe saw the invention, diffusion, or earliest perfection of holding companies, of cash less transactions using bills of exchange, of contracts for marine insurance, and of advanced bookkeeping techniques including so-called "double-entry" accounting. Double-entry bookkeeping is defined as any bookkeeping system in which there was a debit and credit entry for each transaction, or for which the majority of transactions were intended to be of this form. Debit in Latin means "he owes" and credit in Latin means "he trusts". For more historical details, see this essay about Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism, a publication of Harvard Business School, 2017... that we have just cited!

The blockchain is neither more, nor less, than a book of accounts, but dematerialized, eliminating the need for a trusted person to keep the book in a trading centre (by lawyers, attorneys, legal practitioners or persons of this kind, but I'm not very familiar with this population). Let's now dive into the main notions of the blockchain technology!

A hash function is any function that can be used to map data of arbitrary size to fixed-size values. The key idea is to represent a huge quantity of information by a condensed form. A hash function that is injective -- that is, maps each valid input to a different hash value -- is said to be perfect. With such a function one can directly locate the desired entry in a hash table, without any additional searching. The hash function is also required to be collision-resistant, which means that it is very hard to find data that will generate the same hash value. Collision resistance is accomplished in part by generating very large hash values. For example, SHA-2, one of the most widely used cryptographic hash functions, generates 256-bit values.

SHA-2 (Secure Hash Algorithm 2) is a set of cryptographic hash functions designed by the United States National Security Agency (NSA). The SHA-2 family consists of six hash functions with digests (hash values) that are 224, 256, 384 or 512 bits: SHA-224, SHA-256, SHA-384, SHA-512, SHA-512/224, SHA-512/256. To use SHA-256 in order to generate the hash of the text "bonjour les amis", you can do as follows:

# Under MacOs $ echo -n "bonjour les amis" | shasum -a 256 8964605644877dc1ac7b61d119553db099d705dc9a61c872f3a5c86664c01f99 - # With openssl command line $ echo -n "bonjour les amis" | openssl dgst -sha256 (stdin)= 8964605644877dc1ac7b61d119553db099d705dc9a61c872f3a5c86664c01f99 # Note: use echo -n to bypass \n at the end of the string # Note: Openssl version is $ openssl version OpenSSL 1.0.2s 28 May 2019 # Note: do not forgot to update openssl/openssh quite often # to the latest version... for security matters!

The algorithm for computing the hash follows the Merkle-Damgård construction which is an iterative process over "blocks" of predefined sizes (with adding artificial "slot" to align on the size) as it is depicted below:

DHT is a class of a decentralized distributed system that provides a lookup service similar to a hash table: (key, value) pairs are stored in a DHT, like with a dictionary, and any participating node can efficiently retrieve the value associated with a given key. Keys are unique identifiers which map to particular values, which in turn can be anything from addresses, to documents, to arbitrary data.

Appache Cassandra is a good example of DHT which is used to manage huge amount of data. The Apache Cassandra database is the right choice when you need scalability and high availability without compromising performance. Linear scalability and proven fault-tolerance on commodity hardware or cloud infrastructure make it the perfect platform for mission-critical data. Cassandra's support for replicating across multiple datacenters. Please, read this post to become familiar with the Cassandra vocabulary.

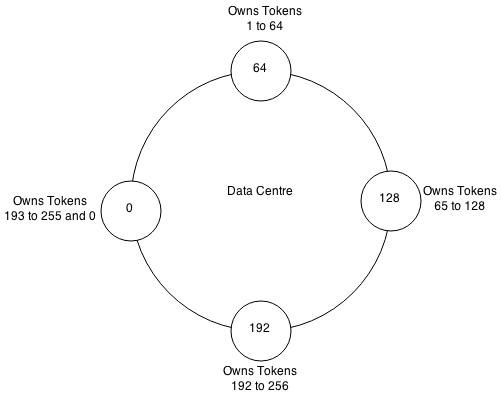

Cassandra DHT is illustrated as follows:

A Cassandra cluster is visualised as a ring because it uses a consistent hashing algorithm to distribute data. At start up each node is assigned a token range which determines its position in the cluster and the rage of data stored by the node. Each node receives a proportionate range of the token ranges to ensure that data is spread evenly across the ring. The figure above illustrates dividing a 0 to 255 token range evenly amongst a four node cluster. Each node is assigned a token and is responsible for token values from the previous token (exclusive) to the node's token (inclusive). Each node in a Cassandra cluster is responsible for a certain set of data which is determined by the partitioner. A partitioner is a hash function for computing the resultant token for a particular row key. This token is then used to determine the node which will store the first replica. Currently Cassandra offers a Murmur3Partitioner (default), RandomPartitioner and a ByteOrderedPartitioner.

A blockchain can be examined as a DHT, with nodes storing Merkle trees and with transations as the data to store, not database tables or documents. Moreover, since the nodes are spread over the Internet, we canno't trust them. We need to add a control over the results they propose to the DHT or the results they produced. The blockchain "proof of work" is one example of such control.

A hash tree or Merkle tree is a tree in which every leaf node is labelled with the hash of a data block, and every non-leaf node is labelled with the cryptographic hash of the labels of its child nodes. In the picture below, the labels are a composition of hashes from children nodes, and where H is a hash function, for instance SHA-256:

You'll notice that the Merkle tree here is a binary tree, most Merkle Trees are binary, but there are non-binary Merkle Trees employed in platforms like Ethereum.

Once built, data can be audited using only the root hash in logarithmic time to the number of leaves. It is because we know that the height of a binary tree with n leaves is in O(log n). Auditing works by recreating the branch containing the piece of data from the root to the piece of data being audited. In the example above, if we wanted to audit c (assuming we have the root hash), we would need to be given H(d) and H(H(a) + H(b)). We would hash c to get H(c), then concatenate H(c) with H(d), then concatenate and hash the result of that with H(H(a) + H(b)). If the result was the same string as the root hash, it would imply that c is truly a part of the data in the Merkle Tree. Otherwise c is not!

The problem the Merkel tree helps to solve is the following. How to be sure that the piece of data you received from peers is part of the collection of data you have requested? Maybe it is fake data! To gain into confidence, send the data to the Merkle Tree. It authenticates the data received from your peers to solve this trust problem.

A Python code to build a Merkle Tree is available online and you can play with it to auditing some data.

This Section is a fork of this lecture which is revelant to understand the concepts of state and transition, in the context of Bitcoin.

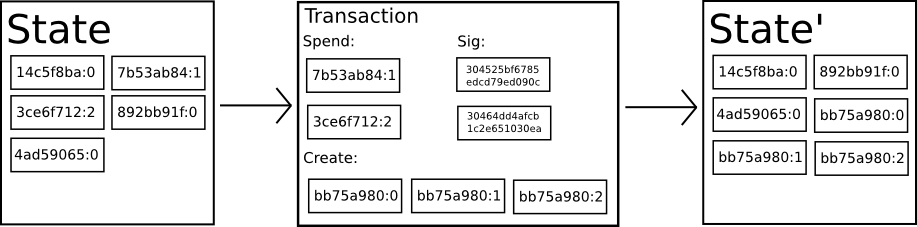

From a technical standpoint, the ledger of a cryptocurrency such as Bitcoin can be thought of as a state transition system, where there is a "state" consisting of the ownership status of all existing bitcoins and a "state transition function" that takes a state and a transaction and outputs a new state which is the result. In a standard banking system, for example, the state is a balance sheet, a transaction is a request to move $X from A to B, and the state transition function reduces the value in A's account by $X and increases the value in B's account by $X. If A's account has less than $X in the first place, the state transition function returns an error. Hence, one can formally define:

APPLY(S,TX) -> S' or ERROR

In the banking system defined above:

APPLY({ Alice: $50, Bob: $50 },"send $20 from Alice to Bob") = { Alice: $30, Bob: $70 }

But:

APPLY({ Alice: $50, Bob: $50 },"send $70 from Alice to Bob") = ERROR

The "state" in Bitcoin is the collection of all coins (technically, "unspent transaction outputs" or UTXO) that have been mined and not yet spent, with each UTXO having a denomination and an owner (defined by a 20-byte address which is essentially a cryptographic public keyfn. 1). A transaction contains one or more inputs, with each input containing a reference to an existing UTXO and a cryptographic signature produced by the private key associated with the owner's address, and one or more outputs, with each output containing a new UTXO to be added to the state.

The state transition function APPLY(S,TX) -> S' can be defined roughly

as follows:

For each input in TX:

S, return an error.If the sum of the denominations of all input UTXO is less than the sum of the denominations of all output UTXO, return an error.

Return S' with all input UTXO removed and all output UTXO added.

The first half of the first step prevents transaction senders from spending coins that do not exist, the second half of the first step prevents transaction senders from spending other people's coins, and the second step enforces conservation of value. In order to use this for payment, the protocol is as follows. Suppose Alice wants to send 11.7 BTC to Bob. First, Alice will look for a set of available UTXO that she owns that totals up to at least 11.7 BTC. Realistically, Alice will not be able to get exactly 11.7 BTC; say that the smallest she can get is 6+4+2=12. She then creates a transaction with those three inputs and two outputs. The first output will be 11.7 BTC with Bob's address as its owner, and the second output will be the remaining 0.3 BTC "change", with the owner being Alice herself.

At large, a consensus algorithm is a process in computer science used to achieve agreement on a single data value among distributed processes or systems or peers. Consensus algorithms are designed to achieve reliability in a network involving multiple unreliable nodes. Processors can fail. The network can fail too. There is different definitions for the faults, but we do not enter into these considerations too much in this note.

Consensus among peers is easy to achieve in a perfect world. The core problem is that there is no way to check whether a peer has failed or whether the peer is alive but the communication to the peer is intolerably slow. This impossibility is proved by Fischer, Lynch, Patterson. Also, in the presence of unreliable communication, consensus is impossible to achieve since we may never be able to communicate with a peer. For further readings, check this page.

In the context of blockchains and bitcoins more specifically since it is related to money, consensus algorithms are used in order to ensure that everyone agrees on the order of transactions. They are also used for keeping track of who owns coins (for the bitcoin case), known as "proof of work". To be short, in the case of applications like a cryptocurrency, this consensus process is critical to prevent double spending or other invalid data being written to the underlying ledger, which, put simply, is a database of all transactions.

Bitcoin's decentralized consensus process requires nodes in the network to continuously attempt to produce packages of transactions called "blocks". The network is intended to produce roughly one block every ten minutes, with each block containing a timestamp, a nonce, a reference to (ie. hash of) the previous block and a list of all of the transactions that have taken place since the previous block. Over time, this creates a persistent, ever-growing, "blockchain" that constantly updates to represent the latest state of the Bitcoin ledger.

The purpose of a consensus mechanism is to verify that information being added to the ledger is valid i.e. the network is in consensus. This ensures that the next block being added represents the most current transactions on the network. The algorithm for checking if a block is valid, expressed in the previous (see Section State, transition, state) formalism, is as follows:

S[0] be the state at the end of the previous block.TX is the block's transaction list with n transactions.

For all i in 0...n-1, set S[i+1] = APPLY(S[i],TX[i]) If any

application returns an error, exit and return false.S[n] as the state at the end of this

block.The key point in the previous algorithm is step 3. The proof of work (POW) is a common consensus algorithm that requires a participant node to prove that the work done and submitted by them qualifies them to receive the right to add new transactions to the blockchain. However, this whole mining mechanism of bitcoin needs high energy consumption and longer processing time. We see in the algorithm that if the POW succeeds, then we can updade the state of the blockchain.

The proof of stake (POS) is another common consensus algorithm that evolved as a low-cost, low-energy consuming alternative to POW algorithm. It involves allocation of responsibility in maintaining the public ledger to a participant node in proportion to the number of virtual currency tokens held by it. However, this comes with a drawback that it promotes cryptocoin saving, instead of spending.

Similarly, there are other consensus algorithms like Proof of Capacity (POC) which allow sharing of memory space of the contributing nodes on the blockchain network. The more memory or hard disk space a node has, the more rights it is granted for maintaining the public ledger.

Note: another possibiliy to reach the consensus is to vote. Here, the idea will be to ask to a subset of miners to produce S[n]. If we get one value that appears at least 51% of times, we elect this value as the new state. With this technique, one problem is to find the "best" number of miners to use in order to tolerate k cheaters.

Miners are peers or nodes that compete to add the next block (a set of transactions) in the blockchain. by racing to solve a extremely difficult cryptographic puzzle. We say that they do mining. Mining is a process of generating proof of work. The first to solve the puzzle, wins the lottery. As a reward for his or her efforts, the miner receives 12.5 newly minted bitcoins - and a small transaction fee. The way it works is that all miners compete to find a number that, when added to the block of transactions, causes this block to hash to a code with certain rare properties. Based on the cryptographic features of the hash function used in this process, finding such a rare number is hard, but verifying its validity when it is found is easy.

With distributed consensus, different legal entities can have a master role (meaning that they are able to validate a transation) but remain in consensus. Three conditions are critical to support this scenario:

To achieve these objectives, the process of consensus follows four steps:

In reality, these steps can be completed in seconds or minutes; Bitcoin takes about 10 minutes. The goal is to get to step four as quickly as possible without breaking consensus.

The main working principles are a complicated mathematical puzzle and a possibility to easily prove the solution. What do you mean a "mathematical puzzle?". It is an issue that requires a lot of computational power to solve. There are a lot of them, for instance to compute hash functions, or how to find the input knowing the output. It works as follows: the miners will run the block's unique header metadata (including timestamp and software version) through a hash function, only changing the 'nonce value', which impacts the resulting hash value. If the miner finds a hash that matches the current target, the miner will be awarded ether (in the case of Ethereum) and broadcast the block across the network for each node to validate and add to their own copy of the ledger. If miner B finds the hash, miner A will stop work on the current block and repeat the process for the next block.

It's difficult for miners to cheat at this game. On the other hand, it takes almost no time for others to verify that the hash value is correct, which is exactly what each node does. This step consists in a traversal of the Merkle Tree. Approximately every 12-15 seconds, a miner finds a block. If miners start to solve the puzzles more quickly or slowly than this, the algorithm automatically readjusts the difficulty of the problem so that miners spring back to roughly the 12-second solution time. To adjust the difficulty, we can play on the nonce value. The mathematical puzzle may consist, as an example, to find a hash with 5 consecutive zeros at the beginning of the hash. Some other methods and examples can be found on this very interesting page.

The difficulty of this work is adjusted so as to limit the rate at which new blocks can be generated by the network to one every 10 minutes. Due to the very low probability of successful generation, this makes it unpredictable which worker computer in the network will be able to generate the next block.

To express some computation or in order to describe transactions we need a language. The language of the bitcoin technology is very (too?) simple and, for instance, there is no loop. The Ethereum (scripting) language) is more elaborated.

A short introduction is available here.

Launched in 2015, Ethereum is the world’s leading programmable blockchain. Like other blockchains, Ethereum has a native cryptocurrency called Ether (ETH). ETH is digital money. Ethereum is programmable (thanks to a powerful scripting language), which means that developers can use it to build new kinds of applications.

The good places to start are:

See Ethereum accounts.

See here.

See Here.

See here (a post on bitcoin.it).

Note: many of the above text is from different authors. If you click on the different links, you will retrieve them. Thanks for their excellent work.